POPLAR GROVE, NOVA SCOTIA, CANADA — It was approaching 9:30 in the morning, and Sara Beanlands was making her way toward the family farm.

Like generations of her mother’s family before her, Sara had traveled this road all her life, but on this occasion the 32-year-old graduate student drove more slowly than usual. She hardly noticed the lush cornfields, the pastures filled with grazing Holsteins or the other familiar landmarks as she navigated the winding two-lane road. It was misty and there was a slight nip to the morning air — not uncommon for the Canadian Maritimes, even in mid-summer — but that wasn’t what gave her a sudden chill.

At the crest of another hill, Sara glanced in her rearview mirror, and the dramatic image that met her eyes made her slow down, turn her head and take in a full, panoramic view. There, stretched out as far down Avondale Road as she could see, was a line of cars and trucks, vans and SUVs, maybe 50 of them, maybe 75, all following her.

She couldn’t help but think, “This is like the longest funeral procession I have ever seen.”

But there would be no funeral this day.

When Sara reached the home of her uncle and aunt, David and Joanne Shaw, she turned into the driveway and the unlikely caravan began pulling in after her. From those vehicles emerged Thibodeaus from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and Quebec and New England, Thibideaus from Ontario, Thibaudauxs from western Canada and Thibodeauxs from California and Texas and — especially — Louisiana.

After they mingled a bit and partook of the pastries, cheeses, coffee, tea and lemonade on the sizable buffet Sara’s aunt, mother and grandmother had set out for them on the deck behind the farmhouse, Sara asked for their attention.

The crowd of happy strangers clustered around her. Looking around, she smiled, perhaps the biggest smile she had ever smiled, and said simply, “Welcome home.”

Upheaval of a people

For the past 2½ centuries, the homeland has not been all that homey for the Acadians.

They called this land Acadie after they arrived from France in the 1600s, developing a successful agrarian society and living in harmony with the native Mi’kmaqs. As control of the region volleyed over the decades between France and England, the Acadians kept their heads down and continued to farm, eschewing politics.

But when war between the two European powers loomed again in the 1750s, the English viewed the Catholic, French-speaking Acadians as a threat. When the Acadians refused to take an unconditional oath of allegiance to the crown, soldiers stripped them of their possessions and launched a years-long forced deportation that became known as le grand derangement.

Soon thereafter, loyal Protestant farming families were induced to relocate from other English colonies down the Eastern Seaboard and were given the farmlands that had been seized from the Acadians.

Some Acadians eventually were allowed to return to Nova Scotia but were shunted in small groups to isolated, inhospitable regions far from their original homes. The repatriated Acadians were suppressed socially, economically and politically, and to this day their descendants are a small and predominantly passive minority in the province.

First-time visitors to Nova Scotia, especially Louisiana’s Cajuns and others of Acadian descent, often seek out sites throughout the Annapolis Valley that are central to Acadian history. Without exception, those places are “English” in character today, with few, if any, Acadians living there and no semblance of Acadian influence in any aspect of everyday life, except at the tourist attractions confected to appeal to unwitting visitors.

A visitor photographs the iconic statue of Evangeline, heroine of Longfellow’s epic poem about the Acadian expulsion, at the deportation memorial in Grand-Pré, Nova Scotia. (Times-Picayune photo by Brett Duke)

The recreated l’Habitation at Port Royal, the thatch-roofed Acadian cottage and dikes at the Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens and the deportation memorial at Grand-Pré are must-see attractions for Acadian pilgrims to Nova Scotia. That such sites are operated in a vacuum within communities that have had little interest in or regard for the Acadian experience is an irony lost on many visitors.

The Congrès Mondial Acadien, the worldwide gathering of Acadians that ended its 16-day run through Nova Scotia last week, was five years in the planning. As the event approached, those willing to discuss the situation would express, at best, a cautious optimism that it might provide, in the long term, a starting point for improved Acadian-English relations in the province. They said it, but they didn’t sound very convincing.

Against that backdrop of how Acadians fit in the modern-day society of Nova Scotia, what happened on Aug. 1 at the Thibodeau family reunion in Grand-Pré and the next day at Poplar Grove, some 15 miles away, was as unlikely as it was inspirational.

Acadian ghosts

Willow Brook Farm has always been an idyllic spot for Sara Beanlands. Growing up a city girl in Halifax, she spent her summers there, cavorting with her cousins, clambering over abandoned farm equipment, hiding in lopsided old barns.

For Sara, there was a comforting feeling about the farm — the hills and pastures, the family togetherness, the farmhouses and barns, even the cows. This was the Shaw family farm, run by her uncles, Allen and David Shaw, and before them by her grandfather, Anthony Shaw.

As she got older, she developed a keen interest in history, and she began to take a more scholarly interest in her family’s history. Her research revealed that Arnold Shaw had been a successful farmer in Little Compton, R.I., until he was recruited by the crown to relocate in Nova Scotia in 1761. Like other hand-picked settlers, he received a land grant for one of the area’s choicest farming sites.

The farm has been in the Shaw family ever since, a rare example of a property remaining in the possession of direct descendants of one of Nova Scotia’s earliest “New England planters.” Uncles Allen and David are the seventh generation of Shaws to farm the property. Generations of Shaw farming families who preceded them are buried in a family cemetery in a grove of trees there.

Sara’s research had been easy, thanks to a bountiful paper trail recording every significant development along the way, back to Arnold Shaw’s acquisition of the farm. Whatever came before that didn’t seem to matter.

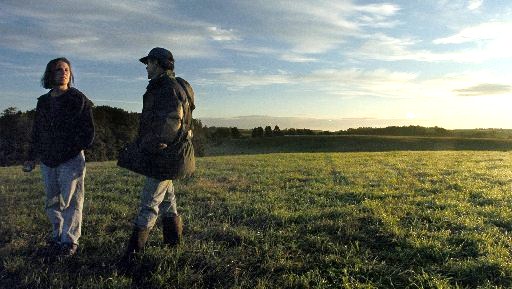

Sara Beanlands and her uncle David Shaw on the family’s WIllow Brook Farm. (Times-Picayune photo by Brett Duke)

Then one night in March of last year, Sara and her parents, Gordon and Hope Beanlands, were back on the farm for a family dinner. Over the course of the evening’s conversation, her Uncle Allen mentioned that he had gotten a recent phone call — out of the blue, after 18 years — from Dick Thibodeau.

Sara’s ears perked up. Who was that? What did he want?

Allen Shaw casually told his niece what older family members had long known. Dick Thibodeau was a man from the States who had turned up at the farm one day back in 1985, clutching a copy of a faded old map and looking for a spot where he believed his Acadian ancestors had lived, prior to the deportation.

Allen had recognized the features on the map and showed him around the farm, helping him locate the places that corresponded to the five dots on his map.

The map was dated 1756. The dots were labeled “Thibodeau Village.”

The man was grateful beyond words. After he’d seen enough, he went home to Massachusetts, Allen went back to the work, and that was that.

Sara had been 13 years old when Dick Thibodeau had come to Willow Brook Farm. Had she even known about his quest at the time, it would have meant nothing to her. But now, as a family historian and a college history major, she found it difficult to take this all in.

An Acadian village? On our farm? When? How? Who?

Unchanged topography

Dick Thibodeau thought he knew where he was going when he took a trip to his father’s hometown in 1973. Vacationing from his job as a serviceman for a natural gas company in Massachusetts, Thibodeau, then 39, drove up to Sorel, Quebec, only to see his life take an unexpected turn down an unfamiliar but beckoning path.

Meeting distant cousins and wandering old cemeteries in search of Canadian relatives’ tombstones, Thibodeau was bitten by the genealogy bug. He soon immersed himself in serious research on his family history, eventually joining three genealogical societies. It wasn’t about gathering names and plotting family trees, though.

“I was more interested in visiting the places where my ancestors had lived,” he recalled this month.

In 1981, Thibodeau made his way up to Windsor, Nova Scotia.

Windsor is best known as the birthplace of ice hockey. Fans come through year-round to buy souvenir wooden hockey pucks and see for themselves where an inspired group of college boys ventured onto a frozen pond around the turn of the 19th century and invented what would become the national sport of Canada.

For him, though, the town was something else entirely. It was the deportation site for one of his ancestors, Alexis Thibodeau.

“I didn’t really expect to find much of anything in Windsor except to be able to say that I had been there and had actually walked on the very ground that my ancestor might have walked upon and been deported from,” he said.

His initial inquiries were fruitless, but his persistence paid off on a second visit in 1982, when a Windsor tourist bureau staffer put him on the phone with Rollie Meuse, a local man active in historical projects. Meuse sent Thibodeau a copy of a crude map drawn one year after the deportations began, showing a “Thibodeau Village” of five dwellings at a distinctive bend in the St. Croix River.

He returned in 1983 in search of the telltale bend in the river, cognizant that the region’s topography might have changed dramatically over almost 230 years due to the river’s dramatic tidal fluctuations induced by the nearby Bay of Fundy.

After a prolonged period of studying his maps, reviewing his homemade videotapes of the area and generally obsessing about it all, Thibodeau turned up at Willow Brook Farm in 1985. Minutes later, Allen Shaw led him to a hilltop overlooking the St. Croix River.

“This is it,” he told himself. “Everything fits. This has to be it.”

When he got back to Massachusetts, Thibodeau was beside himself with excitement over his discovery, but he couldn’t get anyone else interested in it: not his family, not his genealogy club friends, not anyone. Frustrated, he reluctantly put it all behind him as he and his wife set their sights on his retirement and a move to Florida.

He’d think about it again from time to time, though, and one day, years later, he broke down and gave Allen Shaw a call. The farmer was surprised, and while the conversation was altogether pleasant, he had no new light to shed on the matter of the old Acadian settlement. When they said their goodbyes, Dick Thibodeau was convinced he had reached the end of the line.

Subtle clues

Sara was enthralled by the story her uncle related. No one had ever said anything to her about Acadians having lived there before the Shaws.

“You have to understand something about this area: It’s English to the core,” she said later. “You wouldn’t find a French-speaking person there to save your life.”

As she thought about it, though, she realized there were clues, scattered all over Willow Brook Farm.

There were the French coins that got plowed up from time to time. The neat patch of flowers that bloomed in the middle of a pasture every year, where a home must have been long ago. The trail through the farm, down to the river, that locals call the Old French Road. The spot everyone knows as French Orchard Hill.

Even the name Willow Brook Farm harkened back to the willow trees that were brought from France by the Acadians.

Sara had never put it together before, but her uncles knew.

“Nobody knows his land like a farmer,” she said. “These stories were passed on from father to son.

“This was all just not very important to my family at the time. They’re farmers. They’re good people, and they’re good at what they do, but there was just not a good understanding of the history of Nova Scotia or the Acadians.”

Now the niece studying archaeology and pursuing a master’s degree in history understood.

“I am loyal to my family,” she said. “I want their lives to continue as they used to. But I feel compelled to record the Acadian history that is here.”

The first thing Sara did was send a letter to Dick Thibodeau, to get his story first-hand. He called her immediately, and a long-distance partnership was born.

Then she immersed herself in the Thibodeau family history he provided.

She arranged for university archaeologists to excavate for artifacts on the suspected site of one of the Acadian dwellings.

She induced Canadian national parks experts to visit and consider whether the farmhouse where David and Joanne Shaw live is an authentic Acadian dwelling, perhaps the only one to survive the burnings that accompanied the deportation and, barring that, the ravages of time. The design of the house incorporates traditional Acadian characteristics, and it’s the only old house in Poplar Grove that is situated sideways, as if it were built to face some long-gone pathway instead of Avondale Road.

The Parks Canada people sent a section of a support beam from the basement of David and Joanne Shaw’s house to an Arizona laboratory to be age-tested. They suspect it will prove to be a pre-deportation house.

“Family legend says when the Shaws arrived, that house was here. It was an Acadian house,” Sara said. “We’d like to confirm that.”

The dig on the hill overlooking the river revealed a wide array of utensils, smoking pipes and other household items that dated the homesite to 1749.

Research concluded that Thibodeau Village was founded by Pierre Thibodeau in 1690. Pierre, born in 1670, was the oldest son of Pierre Thibodeau and Jeanne Terriot, who came from France to begin the Thibodeau family line in Acadie.

Son Pierre and his wife, Anne Bourg, had 12 children, all at Thibodeau Village. Among them was a son named Alexis, who was separated from his family and shipped off to Philadelphia in the deportation of 1755, 230 years before his descendant, Dick Thibodeau, would walk in his footsteps on Willow Brook Farm.

Opening a dialogue

The opening ceremony for the Congrès Mondial Acadien was Saturday, July 31, in Clare on Nova Scotia’s “French shore.” As with the two prior worldwide gatherings of Acadians — 1994 in New Brunswick, 1999 in Louisiana — family reunions were among the most anticipated of all Congrès events. Almost 100 were scheduled throughout Nova Scotia, and the Thibodeau family chose to gather on Aug. 1 at the deportation memorial park in Grand-Pré.

Dick Thibodeau and Sara had reported what they had uncovered to the reunion committee. They were invited to share their findings at the reunion.

Thibodeau went first, recounting his circuitous search for his roots. Then he alluded to some exciting discoveries about the family’s ancestors, and he introduced Sara to pick up the story.

“I wasn’t sure what was going to happen,” she said later. “I had some really good information, but I had no idea how I would be received. I hoped for the best, but I thought people might be a bit uncomfortable, like, ‘Why are you here when you’re the people who took our lands?’

“I was hoping one or two people might come up when I was done and say thanks, but I was prepared for some negative reaction, too.”

She looked out at the 325 people who had crowded into the huge white tent near the park’s famous statue of Evangeline, took a deep breath, and began:

“This is a story about a landscape shared by two families with a very unique connection to the land and, by extension, to each other for more than 300 years . . .”

Showered with gratitude

Sara had never made a PowerPoint presentation before, and it showed. She was nervous. She got mixed up. She couldn’t get the equipment to work properly. She kept bumping into the microphone. At one point she called her father up to the stage to try to help her get through it.

She muddled on, concluding with a modest invitation for interested family members to drive out to Poplar Grove the next morning and visit the farm. Unable to sense what kind of reaction she was getting from the stoic audience, she feared the worst.

She need not have worried. People started lining up to talk to her before the applause had even died down. Some pressed her for more information, but all of them wanted to thank her for taking such a gratifying and unexpected interest in their family. The receiving line took half an hour to play out. There was not a single negative comment.

The next morning, Sara stationed herself at the Windsor welcome center to meet folks who wanted to see the Thibodeau Village site for themselves. To her utter shock, 10 vehicles turned into 20, then 30, then 40. She gave it a few more minutes, then called her Aunt Joanne with a heads up.

“I’m coming with the Thibodeaus,” she announced.

“What are you talking about?” Joanne Shaw replied. “They’re already here!”

Thirty to forty people from the reunion had bypassed the rendezvous point indicated on the map Sara had distributed and proceeded directly to the farm.

Once Sara arrived with her entourage, what transpired that morning at Willow Brook Farm was magical. There were perhaps 150 descendants of a long-ago Acadian family gathered in that spot, and four generations of the Shaw family went out of their way to make them feel welcome, appreciated, at home.

People marveled at Joanne and David’s Acadian-looking house, rotating in and out of the basement where they took snapshots of the support timbers and the 2-foot-thick stone foundation wall.

They chattered and laughed and got to know their hosts and hostesses. It became an unscheduled extension of the family reunion.

More than 100 of the visitors followed Sara down the Old French Road for a tour of the farm’s Acadian sites. Most of them made it up the hill to Pierre and Anne’s home site, with its stunning view of the environs including that bend in the St. Croix River. Many lingered there, taking more pictures, admiring the scenery, soaking it all in, connecting with the past.

Sara Beanlands leads Thibodeau family members on a tour of Willow Brook Farm. (Photo by Ron Thibodeaux)

“This is the site, ” Sara said. “We’re never going to let it be forgotten again.”

Like many, Don Thibodeaux of Baton Rouge came down the hill with a treasured souvenir: a plastic bag he filled with dirt from the home site on the hilltop. Some of it will go to genealogical societies in Crowley and Opelousas that have particular interests in the Thibodeaux history, but he’ll be keeping the rest for himself and his family.

“It’s amazing,” Marcel Thibodeau, of Meteghan River on Nova Scotia’s French shore, said as he walked down the road back toward the Shaw home. “All my life living in Nova Scotia, I never knew this was here. They had a good life here. This was good for us to see.”

Up ahead, two 7-year-old boys were running up and down the hillside, weaving in and out of the crowd, tossing pebbles, laughing it up and drawing laughs in return. One was Page Thibodeaux, who had come from Mountain View, Calif., with his parents and grandparents. The other was Sara’s cousin Austin, Joanne and David’s grandson.

“It was so symbolic to me, that in 2004, all of these circumstances brought those two boys together to be best friends in that place on that one day,” Sara would say later.

Back at the house, the visitors lingered until well past noon. One by one, two by two, they went on their way — grateful, uplifted — after thanking Sara and her family for making the day’s unforgettable experience possible.

Sara Beanlands with her grandmother, Beulah Shaw, and her mother, Hope Beanlands, at the gathering of Thibodeau family members at Willow Brook Farm. (Photo by Ron Thibodeaux)

Then the gracious Shaw family went back to tending the farm, as Shaws have done there since 1761. There’s something to be said for stability.

But sometimes, things do change, in ways that are unexpected but carry with them a certain symmetry. Sara Beanlands has decided to focus her graduate studies on Nova Scotia’s Acadian history.

“This experience really gave me an understanding of what being an Acadian means,” she said. “This doesn’t happen to people like me.”

“These families are linked by 400 years of history, tragedy, heartbreak, redemption, reconciliation. Who would have thought that for that one day, the Shaws and the Thibodeaus would be one big family?”

. . . . . . .

Originally published in The Times-Picayune, August 23, 2004.

Thank you for this information. I too visited Nova Scotia in September 2015 on the trail of the Thibodeaus. My great grandmother was Lois Thibodeau and her father was Charles Edward Thibodeau (son of Etienne …son of Jean Baptist ….who was born in 1755 ) It was very moving to walk the same area my ancestors once walked. i cried but knew I come from survivors.

LikeLike

I was at the reunion Ron describes in the 2004 article with my wife and son (who is plainly visible in the photo where Sara is talking to a group on the hilltop). It was such a moving day at Thibodeau Village. Sara has become a friend and really a family member to the Thibodeau(x)s. Dick has passed since then, but his contributions to bringing the Thibodeau(x) family together and educating us about this part of our history has been invaluable. And Sara continues to explore our history and legacy on Thibodeau Village through subsequent digs there. Her family is so accommodating to all of us. This relationship between our families that was begun by Dick back in 1984 and blossomed in 2004 is one that I hope continues for many years to come.

LikeLike

I attended the reunion in 2004 at Poplar Grove with my son Mark and wife Paula. We walked up the Old French Road with many other Thibodeau(x)s to the hilltop overlooking the St. Croix River where Sara had conducted an archeological dig and many generations of Thibodeaus and Shaws had farmed. The next summer on their visit to LA, Dick Thibodeaux, Sara, and her parents gave those of us who visited with them some dirt from that hilltop. Over the next few years, I was lucky enough to become friends with both Sara and Dick. Sadly, Dick passed away in 2018 after beginning this melding of the Shaw and Thibodeau(x) families back in 1984. Because of the Shaws’ generosity and hospitality, illustrated so beautifully in this article written by our cousin Ron Thibodeaux that chronicles the 2004 Thibodeau(x) Reunion, the Shaws have become a part of the extended Thibodeau(x) family. As alluded to in the article’s title, our Acadian/Cajun family has most surprisingly found a second home on what was once our ancestral home.

LikeLike

This is very interesting. My direct paternal Pitre ancestors were living at Cobequid prior to the Expulsion, which was also on the shores of the Minas Basin. By 1752 they had taken refuge near Fort Beausejour at Le Lac. As it turns out I do descend from Pierre Thibodeau and Anne Bourg through my 3rd gg Josephine Doiron Pitre/Peters They were my 8th great grandparents. A very moving story about our Thibodeau Acadian ancestors and their descendants reunion where they lived!

LikeLike