Cpl. Paul Thibodeaux stands in front of a jeep at one of the airfields built in Europe by the 843rd Engineer Aviation Battalion during World War II.

Dad loved his work, never complaining about the six days he had to toil every week to keep his small grocery business afloat. He loved to cook — and he was good at it, like so many Cajun men of his generation. He loved the church, taking us to 11 a.m. Mass at St. Gregory every Sunday, always reciting his prayers there in a whisper, as a sign of reverence.

He loved his two sons, and he positively doted on his wife of 46 years.

But there was something else about Paul Thibodeaux. As children, my brother and I certainly admired him for it. As adults, we concluded with amusement that it — much more than parenthood — was the defining experience of his life.

He was a World War II veteran. Nothing, it seemed, ever compared to that.

His particular band of brothers, the 843rd Engineer Aviation Battalion, Army Air Corps, was not a front-line infantry unit. Its members were never dropped behind enemy lines. They stormed no beaches. Their exploits never turned up in a Stephen Ambrose book or a Tom Hanks movie.

They were airstrip builders. As they marched across Europe from 1943 to 1945, soldiers of the 843rd constructed runways and airfield facilities, putting American and British planes ever closer to strategic military targets from France to Germany.

They spent most of their time well away from the battlefront, but that is not to say their duty was without peril. Site preparation for their projects often included the meticulous work of removing unexploded shells, which littered the landscape. They occasionally came under attack from German planes.

But it wasn’t the battle stories that stayed with him. It was the everyday camaraderie, the shared experiences of young American men who came of age during the Great Depression and went off to war with the same mix of bravado, anxiety and patriotism that has defined young soldiers everywhere, in every age.

Journey of the 843rd

The battalion was formed on Sept. 1, 1942 — Dad’s 25th birthday — and he and several hundred other soldiers soon reported to McChord Field near Tacoma, Wash., for intensive, specialized training.

After eight months at McChord, members of the 843rd crossed the country by train, crossed the Atlantic Ocean by ship and crossed Western Europe by deuce-and-a-half and on foot. They slogged through the mud and slept in tents. They danced with British women and learned to drink warm beer. They saw London and Paris and Bob Hope. Through it all, guys named Hotujec from Wisconsin, Brito from New Mexico, Smiljanich from Michigan and Thibodeaux from Louisiana became lifelong friends.

No wonder that, for a farm boy with a limited education who otherwise might never have set foot beyond the isolated bayou country of St. Mary Parish, it was the adventure of a lifetime.

No wonder the VFW magazine, with its calendar of military reunions, was the most eagerly anticipated piece of mail to arrive at our home month after month, year after year, until Dad finally found the 843rd listed there in 1975 and gleefully announced, “Dolores, we’re going to Kansas City!”

No wonder that, in his later years, after easing into retirement, he started dropping hints that he would like to see England and France one more time, if only he could get his older son to take him there.

Almost as soon as he broached the idea, though, he got sick, and nothing more was said about it. After a three-and-a-half-year struggle with cancer, Dad succumbed in 1993 at age 76, departing with only two dreams unrealized. He did not live long enough to dance at the weddings of his three grandchildren. And he never saw Europe again.

Fifteen years later, my wife, Robyn, and I celebrated our 30th anniversary. Empty nesters by this time, we decided to mark the occasion by taking our first trip abroad — to England and France. Once there, I knew what I had to do.

As strangers in a strange land, we were grateful for the hospitality and companionship of longtime friends Hazel and David Lipman, who took us to cheery pubs, the London theater, dinner parties and Windsor Castle. We spent five days with them, went to Paris for five days, then returned to their home in Cranleigh, outside of London, for another week before flying home.

All the while, I maintained a shadow itinerary. Armed with Dad’s wartime photo album, a battalion history he brought back from one of his reunions and a British road atlas, I resolved to visit places where he had served during World War II.

Tracing Dad’s steps

My long and winding road began in Liverpool, the bustling port city where so many GIs first stepped onto European terra firma after a dangerous wartime transit across the Atlantic Ocean. For us, the journey there was a half-day’s drive up the “motorway” — on the wrong side of the road, with the steering wheel on the wrong side of my rental car.

After doing some sightseeing along Liverpool’s Beatles trail, we rode the “ferry ‘cross the Mersey,” made famous in song by Gerry & the Pacemakers, another of those British Invasion groups that provided so much of the soundtrack for our youth. The hour-long excursion up and down the River Mersey, almost to the Irish Sea, provided a panoramic view of miles of riverfront docks.

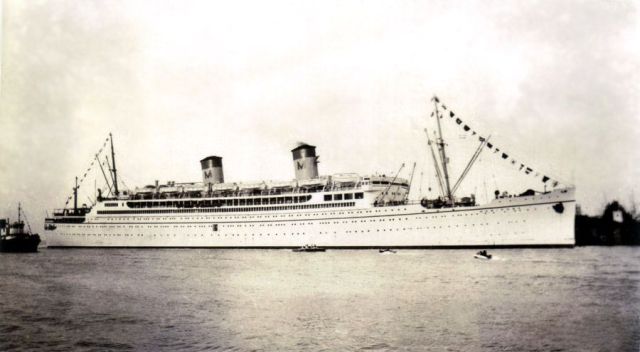

I tried to envision the S.S. Mariposa, a stunning white cruise ship pressed into wartime transport duty, tying up at one of them on June 1, 1943. Cpl. Paul Thibodeaux and his buddies would have been leaning over the railing, waving and tossing packs of American cigarettes to grateful British troops on the docks below while waiting for the order to disembark.

Later that afternoon, their march from ship to train station provided a stark reminder that the GIs had entered a war zone, according to the 843rd’s unit history:

“We marched in silence, looking over our new surroundings; drab buildings, shops, and gaping holes where buildings had stood before the air raids. Liverpool was not a distinguished-looking city; it was a war city that had been hard hit by the Luftwaffe.”

The soldiers boarded a train for their first assignment: completing construction of an airfield at Gosfield, in England’s Essex region. A succession of U.S. and British bomber and fighter units operated out of Gosfield from the airfield’s completion in late 1943 until January 1945. The U.S. 410th Bomber Group was stationed there at the time of the Allied invasion, beginning a series of bombing runs into German-occupied France about five weeks before D-Day.

During the next 13 months, members of the 843rd would crisscross England, building an airfield here, repairing a bomb-damaged runway there, constructing barracks and taking on other projects while the Allied buildup toward D-Day proceeded.

They had ample opportunities to visit London when they were twice stationed nearby, and I found it easy to retrace their footsteps around the landmarks in Dad’s snapshots: Big Ben, Piccadilly Circus, the River Thames bridges, Westminster Abbey.

Walking amid the postcard sights of London, though, I imagined the feel of the city as he must have felt it. The battalion history recalled:

“You walked through the fog in the streets of London in the night or early morning, while sometimes in the blackness overhead planes were droning and searchlights glowed through the fog. On nights when there was a raid the guns slammed ack-ack high over the city, bright showers of incendiaries cascaded down, with the occasional ‘clump, clump’ of heavy bombs. In the pubs as elsewhere the raids were somewhat ignored, and you stayed until the familiar, ‘All right folks. Toime, toime! We’re closin’ up ‘ere now. Toime for a lawst one is all!’ ”

Three weeks after the D-Day invasion, the battalion was ordered to ship out to France. The men of the 843rd spent a night at Romsey, the estate of Lord Louis Mountbatten, then proceeded to the docks at Southampton to load their construction equipment for the English Channel crossing.

Bomb shelters and air raids

City tour guide Don Robertson escorted me through Southampton, which, like London and Liverpool, was another high-priority target for German bombers, due to its strategic port facilities and its aircraft-manufacturing complex.

He proudly showed off medieval churches, a building where Shakespeare is believed to have acted, another where King Henry VIII dallied with Anne Boleyn, a one-time home of Jane Austen and the spot where the Pilgrim fathers set off for America.

He proudly showed off medieval churches, a building where Shakespeare is believed to have acted, another where King Henry VIII dallied with Anne Boleyn, a one-time home of Jane Austen and the spot where the Pilgrim fathers set off for America.

Any bona fide Anglophile would have drooled, but I was more impressed by the dank bomb shelters and Robertson’s dramatic stories of the wartime air raids in his hometown. Even more intriguing was “the American wall,” a brick edifice still decorated with graffiti etched by hundreds of GIs as they waited to board vessels that would carry them to Normandy. I looked for a familiar name, to no avail.

The battalion made an uneventful crossing to Omaha Beach on July 2, a date the soldiers referred to as D-Day Plus 26, and immediately set to work constructing an airstrip for fighter planes near the town of St. Lo. Close to the fighting there, the men slept in pup tents with their M1 rifles loaded and ready. During the ensuing 10 months, they made their way through France and Belgium and into Germany, reaching Munich as the war in Europe ended in early May.

I picked up the trail in Paris, after Robyn and I took the Eurostar train from London through the Channel Tunnel. As in London, I found it easy to hit the famous landmarks Dad had documented in his photo album: the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, Notre Dame Cathedral.

We also spent a day in and around Sacre Coeur Basilica in the city’s charming Montmartre district. Dad’s unit had encamped nearby during its stay in Paris, and my search for the cafes, churches and other neighborhood icons in his grainy black-and-white snapshots proved to be a challenging, time-warped scavenger hunt.

Looking for a legacy

Back in Cranleigh, I took stock of my endeavors. I had seen where Dad had arrived in England, and where he had shoved off for France. I marveled at the same historic sights of London and Paris he had. What was I missing?

It was not just about where he was, and what he saw, I realized. It was also about what he did — his contribution, however modest, to that most noble of 20th century causes.

I had to go to Gosfield.

Whatever remained of the Gosfield Aerodrome, that bomber airfield Dad and the other army engineers had built upon their arrival in England, I needed to seek it out.

It took three hours to reach the village — no bigger than Madisonville, and much more isolated — and I spent another 90 minutes driving aimlessly around the countryside, looking for clues to the airfield’s location. Eventually, a shop clerk sold me a map of the area’s walking trails — part of the public footpaths network extending across all of England — and pointed me in the right direction.

The trail took me past a youth soccer field, along the back fences of residents’ yards, through a dense wooded area and across a pasture. Rounding a thick stand of trees, I continued down a particularly straight section of the trail. I must have walked 50 yards or more before I realized the path was hard-surfaced.

It extended far ahead. Long. Straight. Paved.

Could I be standing on Dad’s airstrip?

I followed it to its end and realized it was an airfield perimeter road that connected to a taxiway that connected with an even wider runway.

Sixty-five years old, cracked, crumbling, severely overgrown and neglected, they were beautiful. I thought of how pleased Dad would have been to know that what he and his fellow soldiers built there had survived all this time later, still used for local recreation. That makes for a respectable legacy, I thought — well, that and saving the world.

In the quiet solitude of that chilly, misty English morning, I hoped the spirit of my father could sense my presence there. I certainly sensed his. I stooped down, patted the weathered concrete a few times, then stood upright again.

“Happy Father’s Day, ” I told him.

. . . . . . .

Originally published in The Times-Picayune, June 21, 2009.

Reblogged this on The Last Full Measure.

LikeLike

Hi Ron,

Came across your blog about your father’s experience during world war 2. I have some photos of the SS Mariposa as a troop ship that I’m sure you’d love to see. If you want them send me your email. My dad sailed on her in 1944 from Camp Miles Standish near Boston to Liverpool before being sent into combat in Italy. My email is williamsarokin@gmail.com

LikeLike

Lovvely blog you have here

LikeLike

Fantastic! My father served with Company A of the 843rd.

LikeLike